Precision medicine pipeline may improve drug treatment for pancreatic cancer

By Hudson Institute communications

A team of scientists and clinicians in Clayton, Melbourne, has optimised a non-invasive technique to screen pancreatic cancer patients for responsiveness to specific drugs, and has commenced a trial with a drug currently used to treat colon cancer in the hope it may be effective in treating up to 10 per cent of pancreatic cancer patients.

The multi-disciplinary team, from Hudson Institute of Medical Research, Monash Health and Monash University, is starting an ambitious Victoria-wide clinical trial to improve treatment for one of the least survivable forms of cancer, pancreatic cancer, and provide some hope to these patients.

“Pancreatic cancer has an overall five year survival rate of around five to seven per cent, which is one of the lowest survival rates of any malignancy. While there have been marginal improvements in treatments, long-term survival rates have remained poor and stagnant over the last 30 years,” said Professor Brendan Jenkins, Research Group Head, Cancer and Immune Signalling at Hudson Institute.

A study, published in the International Journal of Cancer, will form the basis for a trial based at Monash Health, which will screen between 150 to 200 patients recruited from hospitals across Melbourne. The team that worked on the study included first author and Hudson Institute/ Monash SCS PhD student, Mr William Berry.

“If successful, this clinical trial will demonstrate the application of precision medicine – targeting cancer treatment to the genetic profile of the tumour – in pancreatic cancer.”

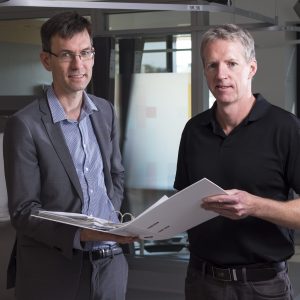

Professor Jenkins and Dr Daniel Croagh, a Monash Health hepatobiliary surgeon who is leading the trial, say it may inform a fast-tracked pipeline for treatment, where biopsies are taken from patients, genetically sequenced and screened for suitability with new drugs, meaning patients could be on a clinical trial within just two weeks.

In this initial trial, tumour samples will be extracted from patients using a technique called endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration (EUS-FNA), then screened for genetic compatibility with the drug treatment being used in the trial.

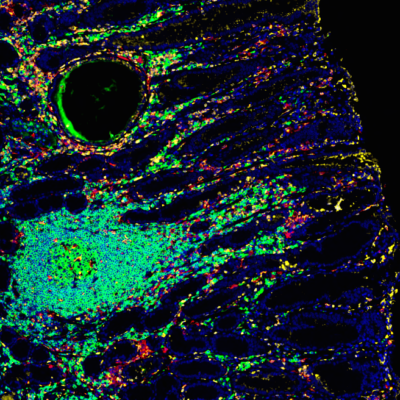

The treatment will be used to target an important receptor called the epidermal growth factor receptor in those patients whose tumours have a non-mutated version of the KRAS gene. These types of tumours make up about 10 per cent of all pancreatic cancers.

“Our ability to extract good-quality genetic material, from small amounts of tissue, is essential to this clinical trial and future trials,” Dr Croagh, who is also a Monash University Senior Lecturer in Surgery, said.

In the study, the team refined the EUS-FNA technique, currently used for diagnosing pancreatic cancer, showing that it can be used to effectively extract high-quality genetic material from virtually any pancreatic cancer patient.

“Currently, less than 50 per cent of patients are able to undergo genetic screening. This is due to challenges in extracting good quality biopsies from patients with inoperable cancers. The new optimised technique can be used to extract tissue from virtually all patients, even those with advanced metastatic cancer,” Dr Croagh said.

The scientists also showed in pre-clinical models that tumours with the normal, non-mutated KRAS gene were responsive to the treatment.

“The treatment being used in the trial works by binding to a protein called the epidermal growth factor receptor, which is found on the surface of normal and tumour cells. In the non-mutated KRAS tumours, it prevents this protein from instructing cancer cells to divide and proliferate,” Professor Jenkins said.

Tumours with a mutant KRAS gene (which make up around 90 per cent of all tumours) were not responsive to the drug. Only patients with the non-mutated KRAS gene will be recruited to the trial, where the treatment will be used as a second-line therapy after standard cancer therapies.

Dr Croagh and Professor Jenkins are hopeful the clinical trial will lead to more targeted treatment approaches to improve responsiveness to drugs and give patients a better chance at surviving longer.

“Pancreatic cancer is a particularly aggressive disease, and a challenging one to treat. The one-size-fits-all treatment approach in place for the last three decades needs to be altered if survival rates are to improve. While there is no silver bullet, we hope this is the beginning of a shift towards better patient outcomes,” they said.

Funding partners | Monash Comprehensive Cancer Consortium, Amgen, Epworth HealthCare, Cook Medical, The CASS Foundation, Illumina.

Collaborating organisations | Monash Health, Hudson Institute of Medical Research, Monash University.

For further information on the clinical trial, please contact | Marion.Harris@monashhealth.org

Contact us

Hudson Institute communications

t: + 61 3 8572 2697

e: communications@hudson.org.au

About Hudson Institute

Hudson Institute’ s research programs deliver in five areas of medical need – inflammation, cancer, reproductive health, newborn health, and hormones and health. More

Hudson News

Get the inside view on discoveries and patient stories

“Thank you Hudson Institute researchers. Your work brings such hope to all women with ovarian cancer knowing that potentially women in the future won't have to go through what we have!”